Collaborative Publishing, a New Model in Independent Presses for a New Age: Conversing with Rose Solari, Alan Squire Publishing

Alan Squire Publishing is an independent literary press that was founded in Bethesda, Maryland in 2010 to publish books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry that are beautifully written and beautifully made, with the avid reader and book lover in mind. They are committed to bringing to the public books of great merit that deserve a wide readership and to collaborating with other independent presses both in the Unites States and abroad. Their primary collaborator is Santa Fe Writers’ Project; others include Chris Andrews Publications Ltd. of Oxford, England, and Left Coast Writers of San Francisco, California.

Rose Solari is the author of three full-length collections of poetry, The Last Girl (forthcoming, November 2014), Orpheus in the Park, and Difficult Weather; the one-act play, Looking for Guenevere, and a novel, A Secret Woman. She has lectured and taught writing workshops at many institutions, including the University of Maryland, St. John’s College, Annapolis, the Jung Society of Washington, and The Centre for Creative Writing at Kellogg College, Oxford University. Her work as a journalist and editor includes numerous freelance assignments, as well as positions as writer and editor for Common Boundary Magazine and as founding editor and writer for SportsFan Magazine.

Her awards include the Randall Jarrell Poetry Prize, and Academy of American Poets’ University Prize, The Columbia Book Award for poetry, and an EMMA award for excellence in journalism. In 2012, she spent two terms as a visiting writer with the Centre for Creative Writing, Kellogg College, Oxford, England, doing research and teaching, and currently serves on the Centre’s Advisory Panel.

Ramola D: We’re delighted to interview you for Delphi, and look forward to learning more about your press. Many of our readers know you as a (brilliant:) poet and some know you also as a compelling fiction writer, with the recent publication of your novel A Secret Woman. You have a background in journalism and in teaching creative writing. In addition, you have ventured in recent years into publishing. Tell us about your press, what it focuses on, and what your vision for it is.

Rose Solari: We – my husband, James J. Patterson and I – founded Alan Squire Publishing in 2010, and went into business in conjunction with Santa Fe Writers’ Project, a press founded by Andrew Gifford that has been around for a little over a decade.

Jimmy and I had already tried one publishing venture together. We founded SportsFan Magazine, a quarterly tabloid focused on the life and times of America’s sports fans, in 1999. We’re both really proud of the magazine, and accomplished a lot, but we decided to move on in 2006.

One of the things we learned was that our skills complement each other’s. I had planned to make my career as an academic, but when I was offered work as a magazine and book editor, I found I was quite good at it. And I love it – I love the thrill of reading a manuscript that is already exciting and well-written, and seeing and feeling how it can be better, stronger, more true to itself. It’s good, solid, satisfying work, and has an element of collaboration that is absent from the writing life, where it’s you and the page together alone every day.

Meanwhile, Jimmy has great business sense – he’s been an entrepreneur since he was in his 20s, first running a media company and then starting a musical act himself. As one half of The Pheromones, the political folk music duo, he learned a lot about marketing and planning tours, in a very boots-on-the-ground way. And he also has a great visual sense – he is the one behind the look and feel of the ASP titles, which are all high-quality paperbacks with French folds, deckle-edged pages, and gorgeous interior and exterior design.

What we share is a deep love and respect for literature, for beautifully written books with challenging and important themes, and a certain irreverence when it comes to accepting whatever the current “wisdom” is about what will and won’t appeal to readers. And of course, a happy willingness to take chances and learn as we go.

Rd: That sounds like such a great approach. Did something in particular inspire you both to move forward from running a sports magazine to starting a literary press? Were other writers involved?

RS: We’d been talking about founding a press for a few years. I was becoming increasingly frustrated and angry about what was happening to some of the books I’d edited, and to some of my writer friends. Some of the books I worked on already had committed publishers, who knew my work and wanted me involved, and that’s great. But sometimes I was hired by a writer who had a publisher but knew they were not going to give the book a thorough edit – there is less and less of that going on these days, as you can see from opening even a big-name title. And I think — we think — that that is awful. If you are published by ASP, you get a thorough and very fine edit.

But even worse, it seems to me, is how many terrific books aren’t getting a chance either because of agents and publishers who are either greedy or have silly, anti-intellectual prejudices against readers. Of the former, I know of at least two fine fantasy writers who were rejected by agents saying they were looking for “the next J.K. Rowling.” To which I’d like to say, rub a lamp. Or really – whatever happened to the old model, where a publishing house that acquired a few big-selling names used that revenue for research and development, for bringing other authors forward? It’s greedy, and it’s lazy. And it’s bad for writer and readers.

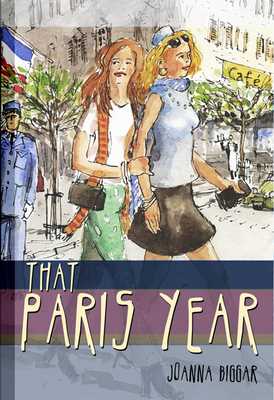

And for the latter here is an example: The first ASP novel, Joanna Biggar’s That Paris Year, is a gorgeously written book  about five young women who spend their junior year abroad in Paris in 1961-62. Joanna has had a long career as a journalist and travel writer, and lived in Paris herself, so she already had fans and credentials; the book has compelling characters, passion, history, sex, great settings, everything. And yet she had more than one agent tell her that Americans aren’t interested in reading about other cultures, which is just jaw-droppingly inaccurate as well as insulting to readers and writers.

about five young women who spend their junior year abroad in Paris in 1961-62. Joanna has had a long career as a journalist and travel writer, and lived in Paris herself, so she already had fans and credentials; the book has compelling characters, passion, history, sex, great settings, everything. And yet she had more than one agent tell her that Americans aren’t interested in reading about other cultures, which is just jaw-droppingly inaccurate as well as insulting to readers and writers.

So all those thoughts were stewing around between Jimmy and me. Then we had a galvanizing moment. In March of ’09, I was invited to serve as Blackwell Books Poet-in-Residence for the annual Oxford Literary Festival. This opportunity was so rich in so many ways, it would be impossible to enumerate them all. But one of the highlights was hearing the publisher John Calder, Beckett’s great champion, speak about his own life and work. He was in his late eighties, and crotchety, but his enthusiasm for his writers was undimmed – he called Beckett “the greatest writer in English since Shakespeare.” That kind of passion is so important.

And when asked his thoughts on the current literary scene, he said that the advances in printing and e-book technology and access have made for “the most exciting time in publishing since the post-war era” of which he was a part. He talked about what might happen when the processes of publishing are democratized, as it were, how opening up those processes to more writers and giving more readers access to books could only be good, and in some unpredictable ways. And he said his only regret was that he might not live long enough to participate in whatever would happen next.

Jimmy and I looked at each other — it seemed we’d heard just what we needed to hear.

On the plane home, we devised a plan to start our own press, involving collaborations with other indie publishers we admired, particularly Andrew Gifford, whom we were just beginning to know. We’d help each other promote and distribute our titles; we’d share experiences, resources, and ideas. We’d keep the name of the umbrella organization under which we’d founded SportsFan Magazine, Alan Squire Publishing, or ASP.

We met with Andrew as soon as we got home. He was particularly interested in a collection of Jimmy’s essays that he was just putting together, Bermuda Shorts. The mix of memoir, pop culture, history, and politics, and the smart and irreverent tone really appealed to him and he thought we should put that out right away.

We met with Andrew as soon as we got home. He was particularly interested in a collection of Jimmy’s essays that he was just putting together, Bermuda Shorts. The mix of memoir, pop culture, history, and politics, and the smart and irreverent tone really appealed to him and he thought we should put that out right away.

I was totally sold on Joanna Biggar’s That Paris Year. So those were our flagship books and we launched them in 2010. Bermuda Shorts quite quickly became an indie bestseller, and Joanna’s book has found a wonderful audience not only in the states but across Europe’s English speakers.

Rd: Your first books were great successes, then. To what extent would you say the press worked toward that recognition?

RS: Well, each of the authors already had potential readers to draw on – Jimmy, from his music career as well as his sports writing, and Joanna as a well-known travel writer and journalist. But we worked with our collaborators to have big, well-attended launches on both coasts – Joanna is a member of Left Coast Writers, and they scheduled several events for us in Oakland and San Francisco that really helped spread the world. And we had a big launch reading and event here in Bethesda that was a great success – in a theater, with music and video in addition to the readings and big party afterwards with good food and wine. It may be the Italian in me, but I think providing your audience with delicious drinks and nibbles is just how it should be.

What else? We send out galleys and press releases, of course. We do a lot of our PR on Facebook, which is terrific for some things, like drawing people to a particular event. And we really drew on each writer’s particular strengths – we were able to book readings for Jimmy where he both read from his book and performed some related songs, singing and playing guitar. This widened the audience by bringing folks who might not think of going to a reading, but who love going to music clubs. Joanna teaches regularly in Europe and Asia, so we were able to get her a reading in Paris and draw on the international audience she had already developed.

It takes a lot of work and imagination and persistence to find these connections and these venues, especially when the core staff is so tiny. But wow, when it works, it is so satisfying.

Rd: So you started with a book of essays and a novel. Do you seek to generally publish a mix of genres–fiction, poetry, memoir–or do you hope to highlight any one genre?

RS: So far the ASP side of things has been all prose – three novels, one book of essays. But in Spring 2015 we’re making our first foray into poetry with a project I’m very excited about — The Richard Peabody Reader. It’s a mixed genre book, with selections from his poetry, fiction and essays, spanning his career. We’re planning an introduction that will give Richard his rightful place in American letters as an important and groundbreaking writer, editor, and publisher, and a time-line of his life and work. Jimmy has always loved that sort of big, comprehensive book, and Richard, with his long dual career of writing in every genre and of ceaseless devotion to other writers and their work is extraordinary. He’s a hero. And we want him to be properly recognized.

That is a big part of our mission in general – to spotlight worthy writers.

We’ve been slow to publish poetry for a couple of reasons. First of all, there are many fine small poetry presses in this country that serve their audiences very well. I believe it is harder in this country right now to get a novel – particularly a big, challenging novel like Joanna Biggar’s – or a collection of essays into print than it is a book of poems. But we have some ideas cooking for new books of poems, possibly some “new and selected” titles. And we’re putting out my next collection, The Last Girl in the fall. I had intended to keep my poetry out of the mix, but our co-publisher Andrew Gifford insisted. So I’ll be a kind of guinea pig for ASP poetry titles, which makes sense.

Another thing we insist on is writers who are willing to get out there and promote their work and that they be good live. Our launches are more like performance events or big arts parties, and our collaborators all help with booking tours and gigs, so we need people who are good on their feet. And if you’re not already confident in your reading ability, we can help you get there. You hear people complain about how many good writers aren’t good readers, but sometimes they just need a bit of coaching. Jimmy and I both have lot of performance experience, and there are all kinds of tips we can offer, from breathing exercises to how to work with a microphone, that can really help an author, especially one who is new to performing. We’ve also invested in our own PA system, so we’re not at the mercy of a particular venue’s sound system, or lack thereof.

Rd: You have recently published UK author Mark Pritchard, and you have an Oxford co-publisher. How did the English connection come about?

RS: Like a lot of the best things in my life, it was completely improvisatory and unplanned. When my second book of poems, Orpheus in the Park came out, I sent off some copies to a few folks I knew in the UK, purely as gifts. One of those people, a very kind and generous lady, wrote to ask me if I’d read from and discuss the book at a private book group she ran in Oxford. Jimmy said, “Well, if we’re going to fly to England, we better get you a book tour.” So we contacted some folks we knew and some we didn’t, and pretty soon, I had a nice little book tour set up from London to Edinburgh. It was an incredible, life-changing experience. And one of the big highlights was a big group reading at Blackwell Books in Oxford, where I was the featured reader along with a great poet and critic there, Lucy Newlyn. The university’s best writers all turned out for it, the place was packed, and I met Lucy as well as Jon Stallworthy, Jamie McKendrick, Jane Draycott, and some other really great poets who are not as well known on this side of the ocean as they should be.

I met Mark Pritchard when I was Poet-in-Residence thing at Blackwell a couple of years later. He read a chunk of his beautiful fantasy novel-in-progress, Billy Christmas, which is a story of a boy’s magical quest to solve the riddle of his  missing dad, at an open reading, and I just loved the tale and the way he was telling it, particularly his portrayal of the deeply compelling hero, Billy. Afterwards, I introduced myself and told him how impressed I was. He had been making the rounds of agents and is one of the folks I mentioned who got the “next J.K. Rowling” comment. So as with Joanna, I thought, here is this wonderful writer with a beautiful and ambitious book, and it would be a shame if no one were to publish this. And Mark is also an actor, so not only is his reading style is gorgeous, but he understood narrative arc and flow from the stage and could bring that to the editing process.

missing dad, at an open reading, and I just loved the tale and the way he was telling it, particularly his portrayal of the deeply compelling hero, Billy. Afterwards, I introduced myself and told him how impressed I was. He had been making the rounds of agents and is one of the folks I mentioned who got the “next J.K. Rowling” comment. So as with Joanna, I thought, here is this wonderful writer with a beautiful and ambitious book, and it would be a shame if no one were to publish this. And Mark is also an actor, so not only is his reading style is gorgeous, but he understood narrative arc and flow from the stage and could bring that to the editing process.

Rd: Does spending time in England influence your views toward a more international kind of publishing?

RS: Oh yes. One of the things that struck me when we were booking that first tour is how much more respect there is in England for small, independent presses. Orpheus in the Park was published by the great Grace Cavalieri and her Bunny & the Crocodile press, and she did a fantastic job, but without a mainstream distributor even my local Barnes & Noble would not carry it. But the folks at Blackwell just said, “Oh, we’ll just order direct from the publisher,” and that was that.

I’ve also become fascinated by the big gap that exists between contemporary British and American poetry. It wasn’t always that way – it seems that since about 1950 or so we’ve untwined our shared considerations in poetry. In fact, that’s what I was researching with the Centre for Creative Writing in Oxford in 2012, under the direction of the Centre’s brilliant and generous founder, Clare Morgan, who is also a terrific novelist. Clare is another person who has opened doors for me in Oxford I could never have walked through on my own. Anyway, it’s turning into a series of essays, maybe a book.

And it has had a profound effect on my own poetry. I’ve been feeling increasingly uncomfortable with much of the poetry being published in the big U.S. poetry magazines these days. I feel there’s been a move toward a kind of obvious cleverness with not much underneath, a resistance to seriousness. I see examples of this everywhere I look – a kind of clever facility with language with not much underneath. I find myself reading more and more U.K. literary magazines and poetry collections these days, and that has been wonderfully inspiring.

Rd: Are there any British poets in particular that you’d recommend American poets read currently?

RS: There are so many, but I’ll just mention three in particular whose work I particularly admire. Jane Griffiths is a poet with, I think, an absolutely original voice, sort of shimmering but practical at once. Her latest, Terrestrial Variations, is a stunner. I am also a big fan of the poetry of Jamie McKendrick, whose work has a subtle intelligence that rewards if not requires re-reading. I loved his collection, Crocodiles and Obelisks. And finally, Jane Draycott, whose last collection, Over, currently resides on a little shelf of books I keep for what is inspiring to me right now. Her poems are somehow elegiac and celebratory at once, and what an ear! She has perfect pitch for the music of poetry.

I would also recommend, more broadly, the presses that publish them: Bloodaxe, Faber & Faber, and Carcanet, respectively. Faber is of course well known here, but all three presses put out wonderful, challenging, all-around excellent poetry. And the publisher of Carcanet, Michael Schmidt, also puts out one of my favorite U.K. poetry magazines, PN Review.

Rd: Those are such great introductions, thank you for sharing that information. Perhaps this will set off a lot of cross-cultural reading and sharing.

Now, has starting the press brought a different dimension to your writing, or would you say they are two separate focuses, necessarily to be kept apart?

RS: I think they are all different parts of one whole. But the press in general has been great for my own writing life. Shepherding good books into print is fabulous inspiration for writing your own. And again, it provides a kind of collaborative relief from the solitary nature of writing.

Rd: How does running a press mesh with your teaching life?

RS: Well, it has pretty much eliminated the teaching part. I do a little individual mentoring these days, but that’s it. That’s all I have time for.

Rd: Moving to some logistics, what is your general selection process for your press? How do you solicit submissions, and what has been the response so far?

RS: For now, ASP is not taking unsolicited admissions. SFWP does, through their annual contests, and we help to screen those.

Rd: How many books have you published so far? Do you have a number you aim for every year, or do you view this as a growing process?

RS: ASP has published four titles so far, with three more to come out in fall 2014/spring 2015. This is definitely a growing process. We are just now meeting to discuss what titles will be next, and there are some tantalizing ideas on the table.

Rd: You sound like such a marvelous press that I am sure our readers would be interested in knowing how you all decide what titles or writers to publish next, and how and when they can participate. (Even if you’re not soliciting submissions right now.)

RS: So far we’ve been drawing on a pool of writers we already knew existed and weren’t getting the attention we thought they deserved, and there are still some folks in that group that we are negotiating with. But I hope to open up to unsolicited submissions in mid-2015, with some specific guidelines. We’re also thinking about doing some samplers – say, three poets or prose writers to one book. We’ll see.

Rd: That sounds interesting. What is your press run like, and how much work do or can you do in terms of distribution and marketing of your titles?

RS: Our press run varies a bit from title to title, but the initial run is never less than 2,000 copies. The great thing about current technology is that you can run a second or third printing quite quickly if you need to, and save money on warehousing books. Andrew Gifford is our distribution person, through Santa Fe Writers project. We have international distribution through IPG because of him, and he works on specific marketing campaigns.

Where our collaborative approach really helps is in promoting book events and sales. Our friends at Left Coast Writers, Linda Watanabe McFerrin and Lowry McFerrin, have set up a couple of great book tours for us, and Chris Andrews is great with bookstore sales and book parties in England. Our events are fun and lively, our writers are great readers, and we sell lots of books when we’re live. What we need now is to develop a second level of marketing strategy, to reach people where we can’t see them. This is what we are focusing on right now.

Rd: What is your business model–do you do most of the work in-house or do you contract out any of the copy-editing, graphics, etc.?

RS: We have a kind of core team that is consistent, book to book, for ASP – Andrew Gifford and his ASP team; Randy Stanard, our book designer; Nita Congress, our copy-editor and layout person; and of course, Jimmy and me.

Andrew, as I said, is our distribution and general publishing business guru. His wisdom and experience have saved us time and many a costly mistake. We could not have done with without him.

Randy and Nita are central to everything we do. Randy gets Jimmy’s visual aesthetic, and brings his own fierce but elegant originality to everything he does. They speak the same language, and they make our books so darn beautiful. And Nita is my ideal editing collaborator. She is so much more than a copy editor, and brings tremendous intelligence to everything she touches, as well as what I can only call a loving eye. She’s as passionate as I am about making the books as good as they can be. And she recently brought Steve Caporaletti, her very able husband, in on the technical side of things, designing e-books in all formats and exploring ways of embedding music, images, and supplemental material into the text. Some very exciting stuff.

We’ve hired other contractors for various things such as print consulting, which has worked well. And we’ve got a good array of outside readers for every book – something that is key if you are going to put your own work into the mix. Again, England is ahead of us on this: Leonard and Virginia Woolf published themselves. John Calder published himself. But that makes the collaborative aspect of what we do all the more important. You have to have someone vetting the projects other than just yourselves. Andrew Gifford is a big fan of both my work and Jimmy’s – it’s part of why he wanted to work with us to begin with – but he’ll tell you right out what he thinks works and what doesn’t. And he has a big group of outside readers that range across genres.

Outside of that, individual readers and editors have played their part in various books.

Rd: In these days of Print on Demand and self-publishing, where it has become easier to publish, what kind of press technology do you use?

RS: For the look and feel ASP is going for, Print on Demand is not an option. And our books are a bit more expensive than other paperbacks, because of the paper, the cover flaps, the deckle edges, and so on. But we look at it this way – those who love not only the contents of books but the feel of a beautifully made one, the beautiful object, between your hands, will buy the book. And those who don’t can get all our titles inexpensively on Kindle. So we’ve got you covered.

Rd: What do you think of the spectrum of book publishing these days? We’ve all heard how the industry is changing, and with all the electronic gadgets we have these days, and all the subsequent new forms being invented–the SMS novel and the hypertext story and the Tweeting poem, no doubt–do you think there’s a future in plain old books and book publishing?

RS: Absolutely. In fact, in the U.S., the sale of actual books is on the rise again, just as new indie bookstores are opening again. I think that tells us something about both publishers and readers.

Rd: And where would you say small, independent houses stand, in relation to the old, big ones?

RS: I think we have a flexibility and autonomy that can serve specific ends particularly well. Most of the small presses I’ve seen succeed know who they are and what they want to publish, and they stay focused and don’t take on too much. At ASP we want smart, challenging, beautifully written fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. If you are in the market for a self-help manual or a gossipy celebrity biography, the big presses have plenty of titles for you. Our titles are not for every reader. But there are a lot of readers out there who are hungry for them.

I think what we’re going through now in publishing is the kind of correction that happened to the music industry in the last couple of decades. I have a lot of musician friends, and I’ve seen how the big labels went from using some of the revenue from their mega-acts to develop new artists to wanting all mega-acts or nothing, and squashing the little guys out. That combined with cheaper recording technology made a kind of revolution possible where recording acts now have many more options. Some of my favorite artists, from Conor Oberst to Radiohead, put out and control their own music now. It’s wonderful.

And now it’s happening in literature. In terms of technology, it’s easier than ever to lay out and print a book.

Rd: The challenge though would be marketing and distribution though, wouldn’t it, and ensuring the book enters the literary landscape through reviews, etc.? I mean, self-publishing in the literary world still doesn’t seem to have the same cachet as being published by a press–maybe it’s different in the music world; how do you see those differences, between a musician putting out their own music and a writer publishing his or her own books? Should writers be more daring?

RS: Well, that lack of cachet, as you put it, I think stems from something I mentioned before: the writer needs to have someone else, someone objective and with high standards, in on the process of vetting and publishing the work. That is why I think the co-publishing model we are working on could be very robust. If the Santa Fe Writers’ Team didn’t think my next book was worthy, it wouldn’t be coming out this autumn. And I also had outside readers on the West coast and in the U.K., who helped to shape the manuscript. So The Last Girl is not a self-published book, but a book put out by a consortium of small presses of which ASP is only a part.

But issues of quality are tricky, aren’t they? I remember eagerly awaiting a new novel by a famous American fiction writer that the press had been touting for months. The first edition hardback had a typo on the first page – the first page! – and the book was discursive, thinly plotted, and highly in need of an edit. And this was from Random House! So I think we as writers really need to ask ourselves some deeper questions about what we think constitutes success in our work and what game we want to be part of.

To give you a very personal example – I was working for a very popular New Age magazine at the height of that movement in the 1990s. I interviewed and edited some very big names in the field for that magazine, and also edited two anthologies of essays there for the lovely and now-defunct Harper-Collins imprint, Harper SanFrancisco. I first got the idea for the novel that would become A Secret Woman in 1996-97. And because I was in a position to meet a lot of powerful agents through them, I had three of them — two in New York one in San Francisco — interested in the book  before I’d written more than a chapter.

before I’d written more than a chapter.

Sounds like a dream, right? Sure. The problem was that each one of them had a very different idea of what the book should be, and none of them sounded quite like the book that was just beginning to take shape in my head. One of them kept talking about how there needed to be lots of sex in it. One of them actually said she could get me a six-figure advance on the strength of a good proposal and I wouldn’t even have to write the book. That’s right – she said we could hire a ghostwriter. Then I’d be free to work on the self-help book she really wanted me to write… (!)

I signed with the third person, rushed to produce a draft for him, and it got some encouraging rejections, you might say, from some big presses. I re-read it, decided it wasn’t at all what I’d wanted, and put it away. It was years later when I took it out again, and decided to start from scratch.

So you can imagine how this experience soured me on any respect I’d had before for the authorities of contemporary literature, be they agents, publishers, or powerful reviewers. And I’ve seen a lot of good friends and good writers waste years in similar processes – being told that if they just write it this way or that way, or if they just write a different book altogether and keep the one they are really immediately invested in for some magical “after that” time, or given any number of other instructions that have the guise of authority but are really utterly ridiculous. But wow, what a waste of time and talent, and how crushing when all those bright plans fail, anyway.

Rd: I know exactly what you mean, having experienced that kind of patronizing and leading on for years myself from agents and editors. Yes, a horrific waste of time and talent. I’m pretty amazed though that an agent would suggest a ghostwriter to you–makes one wonder how many of those books–of questionable worth–by those famous American fiction writers published by the big houses are ghostwritten.

You raise so many interesting questions here, not least the notion that we writers need to question our own definings of success and actively participate ourselves in choosing which game to pursue. It is that kind of thinking also that led to the creation of Delphi Quarterly. Perhaps we can discuss the whole subject more someday on a panel or another interview. Your co-publishing model sounds innovative and intriguing, and something to watch.

RS: That is very interesting – it seems we are both part of the same quiet revolution. John Calder was right – it is an exciting time to be a writer and a publisher. I feel lucky to be where I am, doing what I’m doing.

Rd: As we close, I’d like to bring this back to your own powerful poetry and fiction. Do you feel your artistic vision has been challenged or changed by running a publishing house yourself?

RS: Not changed, but enlarged. I read more widely, and am more ready to take risks in my writing as well as publishing.

Rd: You’ve long had an interest in mythology and also, it seems, in paganism and early cultures. Would these interests be informing your own new work, or are you exploring different directions currently?

RS: Well, Orpheus in the Park is firmly based in classical myth, and my novel A Secret Woman is in part about a woman’s journey to paganism by following her late mother’s trail through London, Oxford, and Glastonbury. So that material is quite clearly itself. The Last Girl, the new book of poems coming out in November this year, certainly has a few echoes of that material, but it’s more elliptical and much less narrative than anything I’ve done in poetry before. It’s as though writing the novel, a long-form narrative, freed the poems to let go of the narrative impulse and make their way in their own new terms, and through other new means.

Rd: That sounds intriguing–I look forward to reading The Last Girl when it comes out!

To close, would you have advice for other writers out there considering the possibilities of starting up a publishing venture?

RS: Have a plan. Set small achievable goals as you strive for bigger ones. Know what you want to accomplish. Publish only books you love – it’s too hard otherwise. If you’re going to put out your own writing, find respected outside readers to vet your work and be sure it’s up to the standards you’d expect from any other good writer. Don’t trust anyone who says they have a magic bullet for sudden success.

And have fun. It’s a marvelous and noble thing to do.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

Visit Rose Solari’s Website.

Visit Alan Squire Publishing on the Web.

Check out the book trailer for Bermuda Shorts, and visit James J. Patterson’s Website.

Check in at the Santa Fe Writers’ Project/Andrew Gifford.

Visit ASP to purchase Joanna Biggar’s That Paris Year.

Visit ASP to purchase Mark Pritchard’s Billy Christmas.

Learn more about John Calder.

Read Jamie McKendrick.